Gavin Beckett, Chief Innovation & Research Officer at Perform Green, looks at how local government can adapt to change and become platform organisations.

I previously wrote about the concept of local government as a platform. It looked at the need to focus on the value propositions and key activities of a platform organisation and how they are significantly different to those of a traditional service delivery organisation.

In this post, I’ll take a more detailed look at what that means. I’ll cover what councils need to be capable of if they are to move away from managing the decline of the service provider model. And I’ll explore how they can nurture creative responses to social, political and economic issues across their localities.

Local government is not just another public service provider in a locality. It has a special role as steward of a resilient and successful place in a competitive global landscape.

The council has to be effective at managing democratic governance and translate community needs and political priorities into strategy. It must build its capabilities as a facilitator to support a platform business model. To enable citizens and service providers to successfully co-create services, the council must engage communities, remove barriers, and ensure space for innovation.

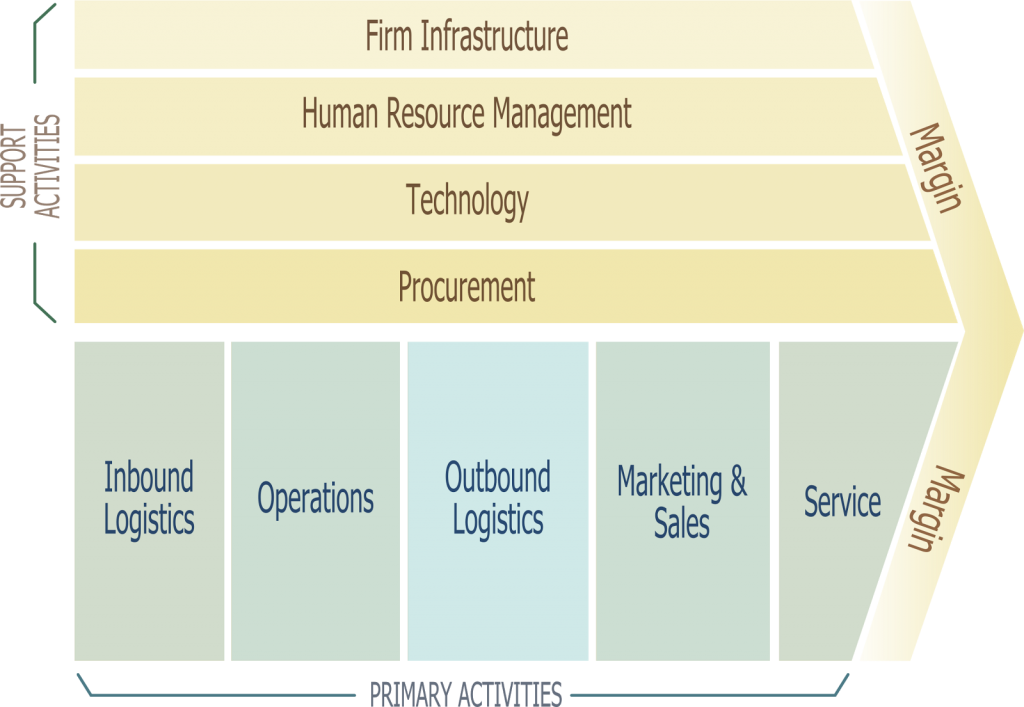

A typical service provider model maps neatly to the traditional management consulting model of the value chain. Inputs are transformed by the operations of the business and outputs are then provided to the market.

This is a relatively simplistic model. It focuses improvement on finding waste and removing it within the organisation. Greater efficiency leads to more value added relative to effort and customers are more satisfied with products and services.

It is immediately obvious that this doesn’t really work in a public service context. We seldom deal with ‘customers’ who want our services and the needs we try to meet are complex and social, rather than consumer wants.

Local government deals in a world of wicked problems and ambiguity. The outcomes we seek may be years or even decades away and many different actors are part of the solution.

So we need to think in terms of an ecosystem – a network of connected communities of interest – all of which have a role to play in creating the problem and the solution. We need to rethink the model of how the council adds value, from a simple chain to being a participant in this ecosystem. Inevitably, that means that a new set of capabilities are required. They must be different to those that a lean service provider would focus on.

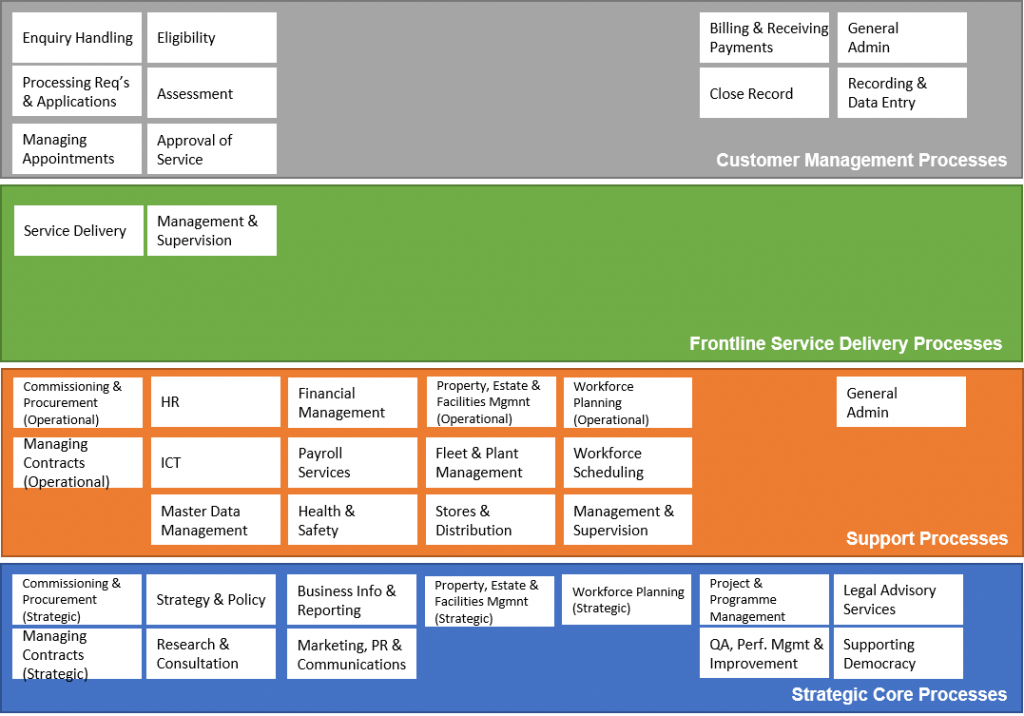

Traditional approaches to business architecture and target operating models (TOM) design see organisations as linear and layered:

Very few councils have internal business architecture, service design or systems thinking practices. Those that have tackled whole-organisation operating model change in the past have tended to work with one of the traditional management consultancies, such as PwC, KPMG, Deloitte, Accenture, Ernst & Young and PA Consulting.

The frameworks and mental models consultancies brought to business architecture or TOM work would typically look something like this:

The work to populate this kind of framework would largely be internally focused. It would involve gathering lots of data about activities and identifying where work was duplicated and fragmented across functions. The aim would be to find and remove inefficiency.

Removing wasteful work that adds no value to our citizens is important, so there can be value in the outputs of such a TOM. But there is a major flaw in this approach that makes it unfit for purpose in the networked society.

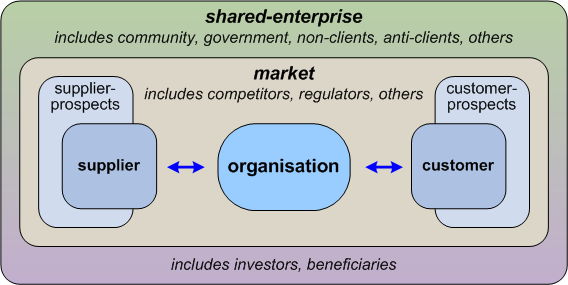

If you conceive the organisation as a box and focus on its internal workings, you miss the essential point that a council is just one part of a wider ecosystem. In fact, this is the case for all organisations, as Tom Graves’s map of the enterprise context space shows.

But it is especially true for local public services, given the wicked problems they are concerned with and the desire to deliver outcomes for communities and localities, not just products and services.

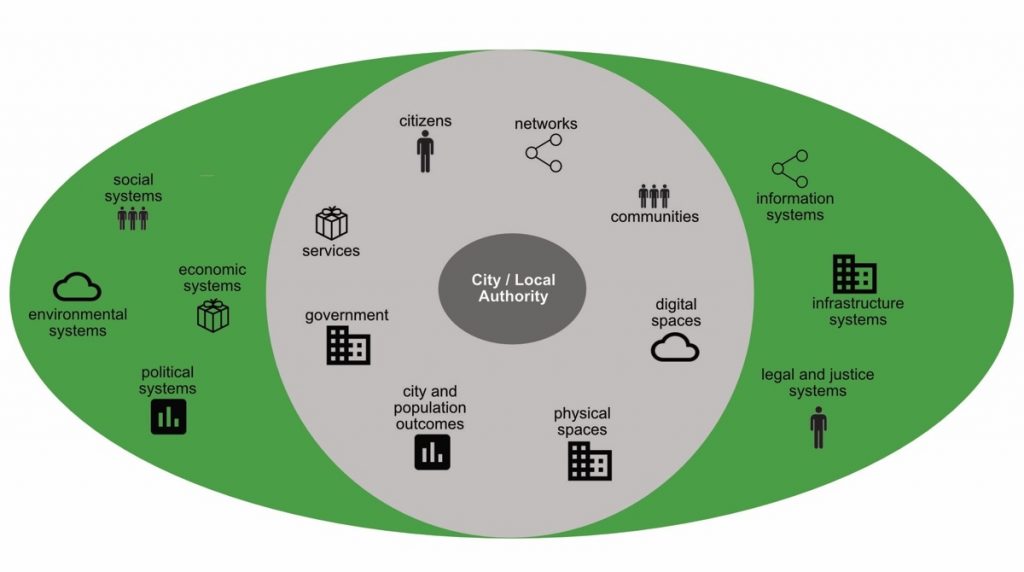

We need to embed the ideas of system leadership that children’s services and the NHS have been working with for some years. We also need to embed the concepts from systems thinking into this new and better model of the business architecture for a council. It starts with the ecosystem and works outside-in (spot the parallel with the idea of starting with user needs).

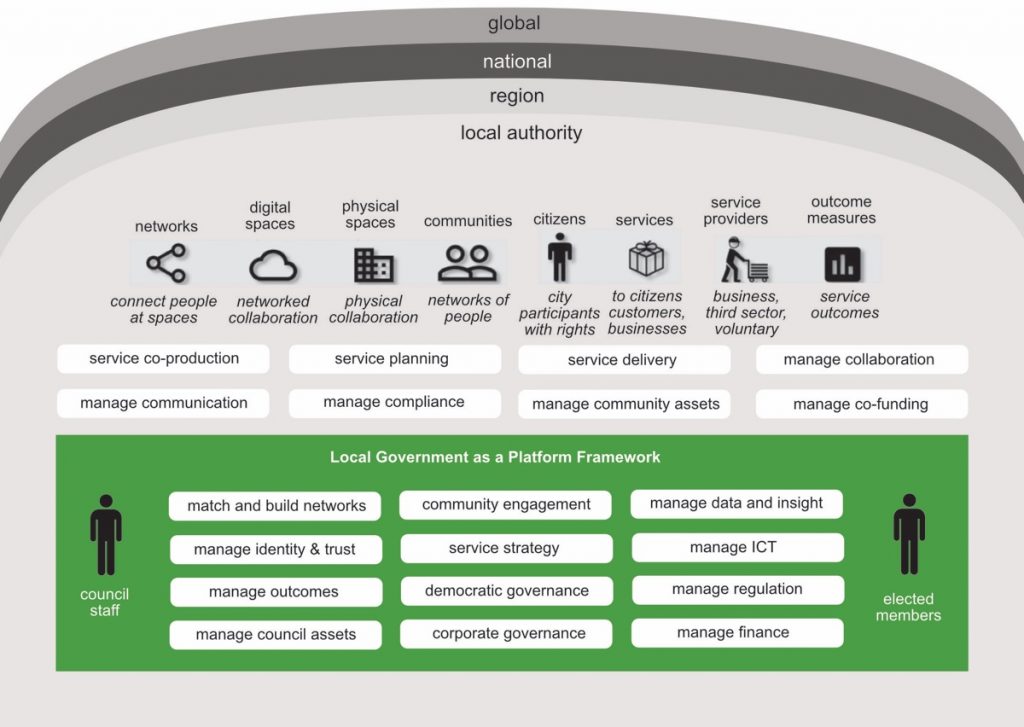

Taking inspiration from Tom Graves’ work on Enterprise Canvas, we can draw a context model and capability model of a local public services ecosystem:

What is the key point of this model? It separates the capabilities of the council into those it must retain, create and improve on. Doing that will allow it to become the system leader and locus of democratic accountability that only local government can be.

The capabilities shown outside of the orange box are necessary for organisations that provide services and support to people and communities. They may come from any part of the ecosystem – public, private, or voluntary/civic.

Is the platform business model just outsourcing by another name?

At this point, I want to take a short detour from my main argument.

I’m aware that I’ve used the same management speak that big consultancies employ in their traditional operating models. I also know that this turns off people who are doing the doing of local public services. It’s also a problem for those who live and work in the communities we’re thinking about.

There is cynicism and suspicion in the local government workforce and amongst critics of government. They will see this as a veneer of words that provide cover for cuts and outsourcing.

On a personal level, nothing could be further from my social and political views. But it’s also really important that we can get beyond this apparent conflict for the success of people and communities living across the UK.

Yes, changing councils from service providers into facilitators means that people working in service delivery jobs will no longer be employed by councils. It may mean that there are fewer of them.

But this is only because a number of the jobs we do are required because there is so much wasteful activity in the system.

So many things provide no value to citizens and are meaningless and boring for staff. For example, several times I’ve seen people employed to print electronic documents and then scan them back into an “electronic document management” system!

Public money – raised from people and businesses (that are full of people) – should not be wasted on this kind of activity. Far from being a right-wing inspired agenda, what I’m trying to define is a creative response to austerity imposed by central government, itself a response to a new economic paradigm.

The local government as a platform approach rejects simple command and control cost-cutting. Instead, it looks for ways that people inside and outside public service organisations can develop real solutions to individual and community problems. The aim is to direct the creativity, time and money in the system towards valuable activities and outcomes.

It’s an approach that embraces public service ethos, community and social value, as well as individual agency. It is aimed more at wellbeing and achieving “the good life” than financial targets. There are strong resonances here with the citizen-centric approach to smart cities and smart society.

The oft-cited example of this in public services is the Dutch health-care organisation, Buurtzorg. There, a large number of motivated and self-directed staff deliver services directly to people with needs. They are supported by a very small number of back-office staff. Buurtzorg’s digital platform helps them reduce wasteful manual paperwork to a minimum.

How can we reshape councils to focus on work that genuinely advances outcomes for people and their communities? It needs everyone working for the council to be doing things that are valuable and necessary. It also needs private and voluntary sector suppliers and partners to be doing the same.

This is not a recipe for unaccountable private companies to provide poor services in pursuit of unwarranted profits. It’s a call for all providers – public, private and voluntary – to be explicitly and publicly measured on their achievement of real outcomes.

Remember that one key hallmark of platform organisations is a transparent customer experience. The age of reference practices seen on platforms such as TripAdvisor, eBay and Amazon Marketplace need translating to more important services that meet citizens and communities needs.

New and improved capabilities of a platform organisation

This brings us back to the capability model. The council, in it’s stewardship role, needs to manage identity, trust and the activities involved in matching and building networks.

Capabilities include the business functions, roles and technology components needed to support the organisations ability to act, so it’s worth looking at some specific areas that underpin a platform business model. How do platform organisations focus their investment differently from service providers?

The Platform Revolution outlines their most important activities and technical enablers:

1. Platforms must support the ‘core interaction’ between producers and consumers, where they exchange information, goods or services, and currency.

- Every platform interaction starts with an exchange of information, through the platform, which enables the participants to decide whether to proceed.

- If they proceed, participants then exchange the goods and/or services that are of value to the consumer. This could be through the platform if they are intangible, but often outside of it. Delivery and receipt is tracked via the platform.

- Finally, participants exchange some form of currency to reflect the value of the goods and/or services. This may be money and payment may be required to route through the platform. It may also be other forms of value, such as ‘likes’ or reviews that add to the standing and reputation of producers.

2. The core interaction involves the participants, the thing that is of value, and the filtering mechanism provided by the platform. This is critical to success. People want to find goods and services that meet their needs quickly and easily.

Enabling this activity technically involves establishing trusted identities of consumers and providers. The same applies to the data and user experience designs that will enable good quality matching of needs with services.

Most successful commercial platforms begin with one core interaction and focus their design on that. Only once they have a critical mass of consumers and providers do they begin to extend outwards to additional interactions that provide more value. How could this work in local government, with its wide range of historic accountabilities? Where would we start?

One option that comes to mind from my experience leading digital transformation in local government is health and social care. This may sound like a very broad and complex area, and in some ways it is. But it’s also been the focus of a lot of thought and local public service design over the past few years, due to increasing needs for these services in all areas of the country.

Most councils, their health system partners, and many suppliers, have looked at ways of bringing together people with needs and service providers through technology. But in most cases, the approach that’s been taken is not one of a platform business model.

Councils either commission service providers to deliver against specific outcomes, deliver services themselves, or provide ‘information, advice and guidance’, online directories that allow people to search for services provided by a wide range of providers.

At first glance, these directories sound like the core of a platform approach. But in most cases, they are not designed around user needs and do not enable an ecosystem of providers to develop and sell products and services directly, with the council acting as the platform broker, governing quality and ensuring trust.

When I last looked at the products and services in this market, only one supplier had broken the mould. They designed their solution around needs as people would express them, enabling them to find and rate service providers. They’d built the embryo of a technology platform.

But this is a starting point. If the tools needed for councils to manage identity, trust and matching across the platform ecosystem were developed, we could see this grow into a new approach that has a significant impact.

Other articles by Gavin for Perform Green:

- Changing the local government technology market

- From Smart Cities to Smart Societies — The Story so Far

- Can We Still Talk about Digital Transformation?